By Matthew S. Lawrence - Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary

August 26 – September 2, 2010

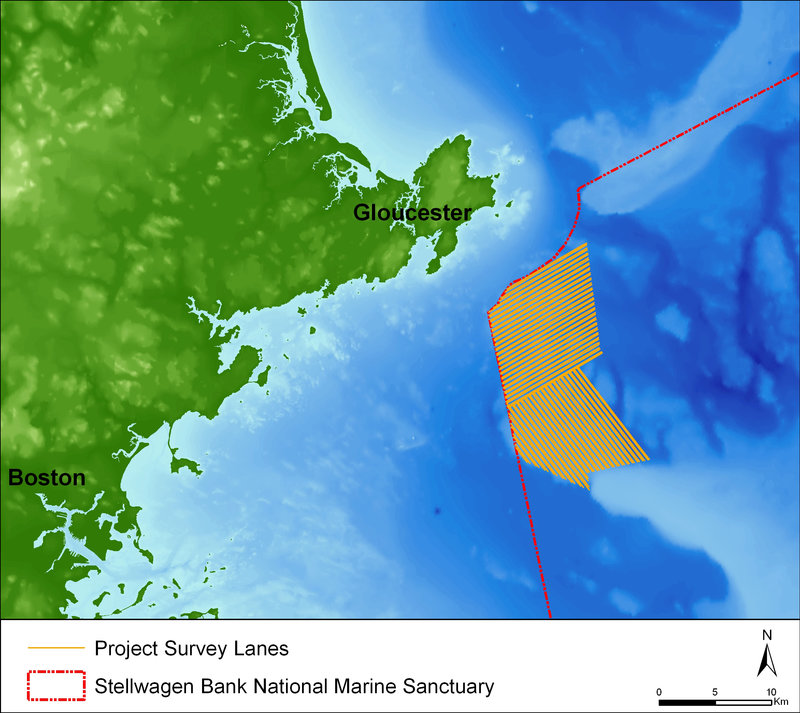

The Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary spans the mouth of Massachusetts Bay between Cape Cod and Cape Ann. Image courtesy of NOAA/SBNMS. Download image (jpg, 144 KB).

The Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (SBNMS) sits astride the historic shipping routes used by mariners to access many of Massachusetts’ oldest ports. Beginning with the European colonization nearly four hundred years ago, much of New England’s maritime traffic has moved through the sanctuary. This high density of vessels combined with stormy weather and human error has resulted in the loss of hundreds of vessels. Locating these shipwrecks is challenging; sanctuary depths range from 25 to 180 meters (m) and the offshore waters provide few geographic references for location. Furthermore, many vessels simply disappeared without a trace. Lacking clearly defined vessel losses, this project sought to map the seafloor on the approaches to the historic ports of Gloucester, Salem, Marblehead, and Boston. Sanctuary archaeologists believed that high resolution systematic survey of a large area along the shipping routes used by Massachusetts’ oldest ports was the best way to locate historic shipwrecks and possibly a shipwreck from the earliest periods of United States history.

Archaeologists began inventorying SBNMS shipwrecks in 2002 to meet NOAA’s mandates arising from Section 110 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. These efforts mapped seven percent of the sanctuary’s seafloor and located 35 historic vessels, but truly large scale surveys had not been undertaken. Investigating the sanctuary’s entire seafloor with conventional marine archaeological remote sensing methodology would require decades at its current pace; therefore, this project sought to employ a highly advanced synthetic aperture sonar (SAS) to map the approaches to some of America’s oldest ports.

SAS technology exemplifies recent advances in geophysical survey technology that will revolutionize seafloor mapping. Stellwagen Bank sanctuary partnered with Applied Signal Technology, Inc. (AST) to use this technology under real-world conditions. AST has developed a synthetic aperture sonar, named PROSAS that can map large areas of the seafloor with high resolution at a very rapid pace. SAS creates acoustic images similar to conventional side scan sonar, but the seafloor images are much higher resolution over large areas. PROSAS can resolve objects as small as 0.03 m-squared and unlike conventional side scan sonar, the sonar’s resolution remains constant out to the edge of its 150 m range. AST combined their SAS with the MacArtney FOCUS-2 remotely operated tow vehicle (ROTV) to create an integrated towed acoustic imaging device, the PROSAS Surveyor. The FOCUS-2 ROTV operates like an underwater box kite providing stability for the SAS multi-ping processing. Furthermore, the dynamically controlled towfish can maintain a precise altitude and track over varying topography and against currents. The PROSAS Surveyor generates highly detailed seafloor maps that may reveal even the oldest historic shipwrecks, particularly in the project area where sedimentation is limited.

The PROSAS Surveyor towfish operates much like a box kite and provides tremendous stability for synthetic aperture sonar processing. The sonar’s transducer arrays are situated on both sides of the tow vehicle’s lower hulls. Image courtesy of NOAA/SBNMS and Applied Signal Technology, Inc. Download larger version (jpg, 8.2 MB).

The project’s survey platform was the research vessel SRVx, operated by the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (see slideshow image 21). The SRVx measured 85 feet long by 23 feet wide. Its stern well deck, spanned by an A-frame, proved to be an ideal launch and recovery area for the PROSAS Surveyor towfish. Mounted aft of the wheelhouse, the PROSAS surveyor winch could be locally controlled during launch and recovery or remotely controlled while surveying. Sonar technicians controlled survey operations from the vessel’s drylab space at two stations. The first station controlled the operation of the ROTV and survey line navigation. The second station recorded and displayed the sonar data and allowed project researchers to study and log sonar contacts (see slideshow images 4 and 15).

This map depicts the survey lanes completed during the project. In total, the project mapped 169 square kilometers of seafloor, equal to 7.7 % of the sanctuary’s total area. Image courtesy of NOAA/SBNMS and Applied Signal Technology, Inc. Download larger version (jpg, 2.1 MB).

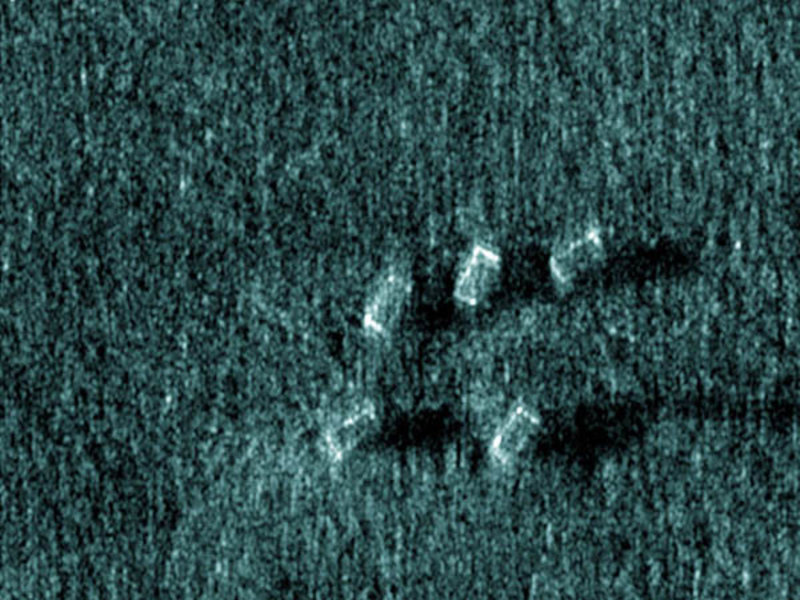

This sonar image of five derelict lobster traps was one of many examples of derelict fishing gear found during the survey. Image courtesy of NOAA/SBNMS and Applied Signal Technology, Inc. Download image (jpg, 164 KB).

Prior to beginning the survey, the project team developed a survey line plan to govern the path of the SRVx and the PROSAS Surveyor. Using the known seafloor bathymetry in the survey area, the team plotted survey lanes that follow the contours of the seafloor. Towed sonars produce the best data when the instrument maintains a constant altitude, sharp rises in the seafloor are particularly problematic as surveyors are fearful of crashing the towfish into the seafloor and potentially losing a very expensive piece of equipment. Survey lanes were separated by alternating distances of 130 m and 280 m. The PROSAS Surveyor was capable of mapping a swath of seafloor 300 m wide; however, SAS cannot map the seafloor directly under the towfish. This unmapped area is known as nadir. Therefore, each lane separated by a distance of 130 m mapped the nadir of its neighboring lane.

The Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary spans the mouth of Massachusetts Bay between Cape Cod and Cape Ann. Image courtesy of NOAA/SBNMS. Download image (jpg, 163 KB).

Upon arriving at the survey area, the project team readied its equipment to begin collecting data. Team members deployed the ultrashort baseline (USBL) transponder on a pole mount off the SRVx’s portside (see slideshow image 1), and readied the towfish’s navigation sensors. When all of the PROSAS Surveyor’s components were online, the team deployed the sonar towfish from the SRVx’s stern well deck. Using the vessel’s A-frame and the PROSAS Surveyor’s winch in concert, team members lowered the towfish into the water after first stabilizing it with a drogue. Technicians slowly payed out the sonar’s armored towcable while the FOCUS-2 towfish’s fins were set to dive the vehicle. Depending upon the seafloor’s depth, 200 m to 300 m of tow cable were payed out to achieve the proper towing altitude.

Crew members rotated shifts every 8 hours as survey operations ran 24 hours a day. Typically, two members of the vessel’s crew and 2 scientists were on duty at any given time. Surveying with a towed sonar can be stressful as it mixes long hours of watching a computer screen with random moments of heart-pumping action. The action usually results when the sonar towfish is snagged by a piece of fixed fishing gear, like the rope connecting a lobster trap to its surface buoy. The fishing gear can damage the very expensive sonar towfish or even cause its loss, so quick action is needed. When the towfish is “hung up,” the project team must swiftly slow the research vessel and carefully winch in the towfish to free it from the entangling gear. Unfortunately, not all fixed fishing gear is marked with an easily visible buoy. The project snagged the towfish several times, especially during night time operations, but the towfish only received slight damage.

The PROSAS Surveyor provided the most detailed sonar image of the steamship Portland yet made. Please visit http://stellwagen.noaa.gov/maritime/portland.html for more information on this vessel. Image courtesy of NOAA/SBNMS and Applied Signal Technology, Inc. Download image (jpg, 195 KB).

The PROSAS Surveyor’s imaging capabilities were put to the test on the previously located shipwreck of the Frank A. Palmer and Louise B. Crary. These coal schooners collided and sank in 1902. Please visit http://stellwagen.noaa.gov/maritime/palmercrary.html for more information on these vessels. Image courtesy of NOAA/SBNMS and Applied Signal Technology, Inc. Download image (jpg, 190 KB).

First and foremost, the project set out to conduct a systematic survey of a specific piece of seafloor off Cape Ann. While initial plans estimated that 200 square-kilometer of seafloor could be covered during the time allotted; only 169 square-kilometers were ultimately mapped (see slideshow image 19 for the completed line plan). While data analysis has not been completed, over a dozen sonar targets with archaeological resource characteristics were found so far within the survey area. These sonar targets will form the basis for future archaeological investigation. In many cases, geologic features may look like potential shipwrecks, particularly the oldest shipwrecks whose wooden hulls have deteriorated significantly over time. Further investigation with magnetometers and remotely operated vehicles is sometimes the only way to differentiate a shipwreck from a pile of rocks.

Maritime archaeologists are continually searching for new technologies to improve their research. Theoretical improvements in technology suggest possibilities for new research methodologies; however, real world application of these technologies is the true test. Oftentimes, technologies that work in a controlled lab setting cannot withstand the rigors of field deployment. This project’s results indicated that the PROSAS Surveyor is a viable tool for large area survey and that SAS technology offers significant advantages over conventional side scan sonar survey. SAS technology was also tested for its imaging capabilities. The team re-imaged the previously located wreck of the steamship Portland and collided remains of the coal schooners Frank A. Palmer and Louise B. Crary. SAS revealed new aspects of both wreck sites and resulted in the most detailed sonar images yet made of these wrecks (see slideshow image 18 for the Portland's SAS image and image 17 for the Frank A. Palmer and Louise B. Crary).

In addition to locating historic shipwrecks, the project’s seafloor maps are also informing the sanctuary’s efforts to assess derelict fishing gear concentrations. Commercial fisheries have left a legacy of derelict fishing gear (DFG). Since the introduction of synthetic material into fishing equipment, lost fishing gear has become a menace to sanctuary marine life. Lost gillnets continue to catch and kill fish and floating line from lobster traps entangles whales. The high resolution acoustic maps generated by the PROSAS Surveyor have revealed large numbers of lost lobster traps and smaller numbers of lost nets (see slideshow image 16 for an image of several lost lobster traps). These items can now be removed from the marine environment. Furthermore, the SAS data will allow the SBNMS to attempt removal of DFG without fear that the gear is entangled in a historic shipwreck.